Study in animals identifies a potential way to build vaccines to fight future pandemics

A potential new vaccine developed by members of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute has proven effective in protecting monkeys and mice from a variety of coronavirus infections -- including SARS-CoV-2 as well as the original SARS-CoV-1 and related bat coronaviruses that could potentially cause the next pandemic.

The new vaccine, called a pan-coronavirus vaccine, triggers neutralizing antibodies via a nanoparticle. The nanoparticle is composed of the coronavirus part that allows it to bind to the body’s cell receptors, and is formulated with a chemical booster called an adjuvant. Success in primates is highly relevant to humans.

The findings appear Monday, May 10 in the journal Nature.

“We began this work last spring with the understanding that, like all viruses, mutations would occur in the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which causes COVID-19,” said senior author Barton F. Haynes, M.D., director of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute (DHVI). “The mRNA vaccines were already under development, so we were looking for ways to sustain their efficacy once those variants appeared.

“This approach not only provided protection against SARS-CoV-2, but the antibodies induced by the vaccine also neutralized variants of concern that originated in the United Kingdom, South Africa and Brazil,” Haynes said. “And the induced antibodies reacted with quite a large panel of coronaviruses.”

Haynes and colleagues, including lead author Kevin Saunders, Ph.D., director of research at DHVI, built on earlier studies involving SARS, the respiratory illness caused by a coronavirus called SARS-CoV-1. They found a person who had been infected with SARS developed antibodies capable of neutralizing multiple coronaviruses, suggesting that a pan-coronavirus might be possible.

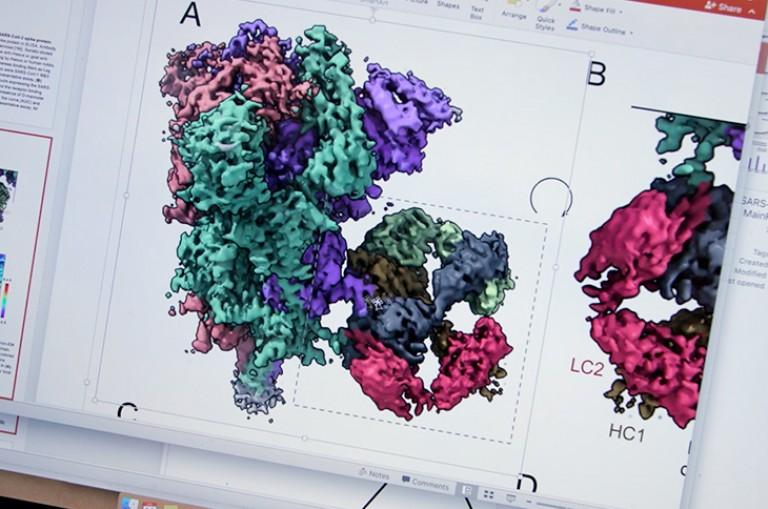

The Achilles heel for the coronaviruses is their receptor-binding domain, located on the spike that links the viruses to receptors in human cells. While this binding site enables it to enter the body and cause infection, it can also be targeted by antibodies.

The research team identified one particular receptor-binding domain site that is present on SARS-CoV-2, its circulating variants and SARS-related bat viruses that makes them highly vulnerable to cross-neutralizing antibodies.

The team then designed a nanoparticle displaying this vulnerable spot. The nanoparticle is combined with a small molecule adjuvant -- specifically, the toll-like receptor 7 and 8 agonist called 3M-052, formulated with Alum, which was developed by 3M and the Infectious Disease Research Institute. The adjuvant boosts the body’s immune response.

In tests of its effect on monkeys, the nanoparticle vaccine blocked COVID-19 infection by 100%. The new vaccine also elicited significantly higher neutralizing levels in the animals than current vaccine platforms or natural infection in humans.

“Basically what we’ve done is take multiple copies of a small part of the coronavirus to make the body’s immune system respond to it in a heightened way,” Saunders said. “We found that not only did that increase the body’s ability to inhibit the virus from causing infection, but it also targets this cross-reactive site of vulnerability on the spike protein more frequently. We think that’s why this vaccine is effective against SARS-CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2 and at least four of its common variants, plus additional animal coronaviruses.”

“There have been three coronavirus epidemics in the past 20 years, so there is a need to develop effective vaccines that can target these pathogens prior to the next pandemic,” Haynes said. “This work represents a platform that could prevent, rapidly temper, or extinguish a pandemic.”

In addition to Haynes and Saunders, study authors include Esther Lee, Robert Parks1,5, David R. Martinez, Dapeng, Haiyan Chen, Robert J. Edwards, Sophie Gobeil, Maggie Barr, Katayoun Mansour, S. Munir Alam, Laura L. Sutherland, Fangping Cai, Aja M. Sanzone, Madison Berry, Kartik Manne, Kevin W. Bock, Mahnaz Minai, Bianca M. Nagata, Anyway B. Kapingidza, Mihai Azoitei, Longping V. Tse, Trevor D. Scobey, Rachel L. Spreng, R. Wes Rountree, C. Todd DeMarco, Thomas N. Denny, Christopher W. Woods, Elizabeth W. Petzold, Thomas H. Oguin III, Gregory D. Sempowski, Matthew Gagne, Daniel C. Douek, Mark A. Tomai, Christopher B. Fox, Robert Seder, Kevin Wiehe, Drew Weissman, Norbert Pardi, Hana Golding, Surender Khurana, Priyamvada Acharya, Hanne Andersen, Mark G. Lewis, Ian N. Moore, David C. Montefiori and Ralph S. Baric.

The study received funding from the State of North Carolina with funds from the federal CARES Act; the National Institutes of Health (AI142596, R01AI157155 U54 CA260543, F32 AI152296, T32 AI007151); the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill with funding from the North Carolina Coronavirus Relief Fund; and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Postdoctoral Enrichment Program Award. COVID sample processing was performed in the Duke Regional Biocontainment Laboratory, which received partial support for construction from the NIH/NIAD (UC6AI058607) with support from a cooperative agreement with DOD/DARPA (HR0011-17-2-0069).