STEPHEN SCHRAMM @WORKINGATDUKE

Duke Associate Professor of Biology Steve Haase likes to compare the spread of COVID-19 to the haphazard advance of a forest fire, where tiny glowing embers, which he likens to the virus, drift in the air, among trees bringing potential harm whatever they touch.

“But here’s the tricky part,” said Haase, part of the team organizing Duke’s COVID-19 surveillance testing program. “Our trees, in this metaphor, are moving around campus. So learning about how these populations move around helps us understand how the virus can spread.”

Duke’s effort to track COVID-19’s presence in the campus community opens up a new front this week as the university begins an ambitious, semester-long surveillance testing program. Starting this week, around 2,000 self-administered COVID-19 tests will be completed by a cross-section of Duke undergraduate students on campus. By end of September, the testing will expand to include undergraduate, graduate and professional students as well as faculty and staff who report to work on campus and interact with students.

There are 11 sites like these on Duke's campus where the self-administered COVID-19 test will be available. Photo by Jared Lazarus, University Communications.

The result of surveillance testing will be a better understanding of where the virus is on Duke’s campus and how it’s being transmitted.

“This is designed to allow us to quickly identify potential hotspots,” Duke University President Vincent E. Price said during Friday’s online discussions with fellow Duke leaders. “It captures people who are not exhibiting symptoms. It’s a survey tool. It lets us take the necessary steps we need to protect the Duke community.”

Surveillance testing is the newest piece of Duke’s comprehensive testing program. Duke already tested all residential students upon arrival to campus and requires students living off campus to be tested before they can attend classes. Testing for graduate students returning to campus will begin this week.

For the past several months, Duke also tested any student, staff or faculty member who shows COVID-19 symptoms and, through contact tracing, arranges testing for Duke community members exposed to someone who tests positive.

But by regularly testing a large sampling of asymptomatic members of the campus community, the surveillance testing program will give Duke a more complete picture

“Surveillance testing has been used for years related to infectious diseases,” said Thomas Denny, Duke professor of medicine and chief operating officer of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute. “It’s a way to get a rapid sense of what’s going on in an area and how much of a pathogen is circulating in your environment.”

The surveillance testing process begins with emails informing Duke community members of an upcoming test, which take place at one of 11 testing sites on campus. After self-administering the test, which involves a nasal swab, the individual verifies their identity and deposits the test in a receptacle The test then heads to the labs of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute for processing.

Results are known in about 48 hours and only those with a positive test are contacted.

The results are made available to a team of experts, who include Associate Professor of Biology Steve Haase as well as faculty from the Duke Department of Mathematics, Duke Department of Population Health Sciences and the Duke University School of Medicine. They will use the data to build models that will help focus the selection of people selected for future surveillance tests and guide university decisions about how to combat the virus.

“The whole idea is to try to adapt the strategy and the people we’re testing to what we’re seeing in the data,” said Tony Moody, associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Infectious Diseases and one of the organizers of the surveillance testing program. “If we’re continuing to see no positives, then it will continue to be a random sampling of people. But if we’re seeing positives popping up, then testing will likely pick up a little bit and we’ll more intensively sample certain parts of campus.”

As the central processor of the tests, the Duke Human Vaccine Institute will use a more efficient pool testing system, which tests several samples simultaneously. It also uses a testing platform that doesn’t use components sourced from the same supply chains health care providers rely on for clinical tests.

“What we’re doing, we’re doing outside of the health system,” said Denny, the professor of medicine and chief operating officer of the Duke Human Vaccine Institute. “We’re not jeopardizing any clinical testing needs by testing 10,000 people a week. We’re not taking 10,000 tests away from people who need them in a hospital setting because they’re symptomatic.”

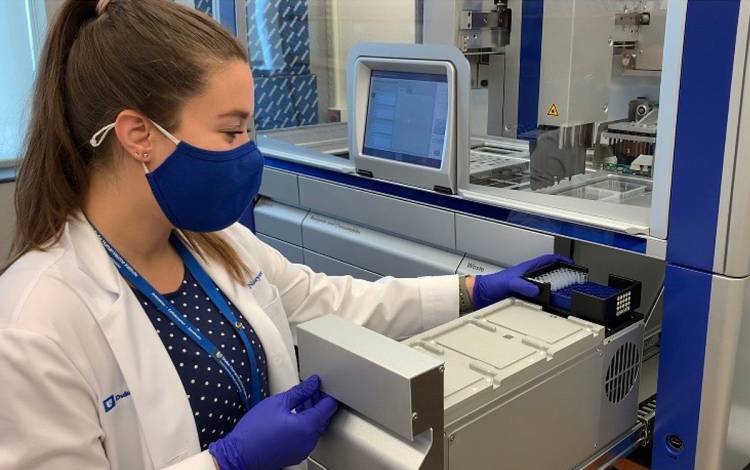

The Duke Human Vaccine Institute is the central processor of the tests. Photo courtesy of Duke Human Vaccine Institute.

The Duke Human Vaccine Institute has enough testing supplies on hand to last until the end of the fall semester. And those tests represent a key piece of Duke’s effort to ensure that the fall semester moves forward as safely as possible.